The Branches in Git explained the basics of how branches works in Git, and how they are very lightweight. If you are working by yourself, branches can be a convenience to keep yourself organised. However, if you work in a small team, meaning from 2 or more developers working at the same time, then you should use local branches to keep a smooth work flow.

Small team working without branches

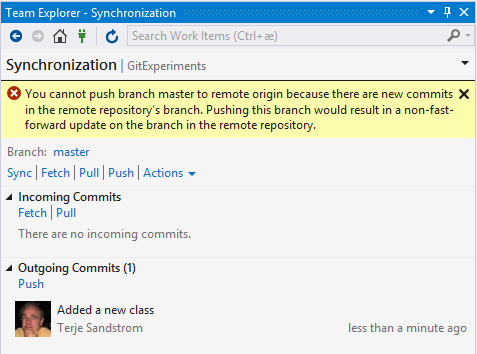

Two persons cooperates on working with the code. One pushes up his commit, and the other tries to commit his, but is rewarded with a message saying he can’t push, because there already are changes on the remote.

This is the same as with TFS VC, you need to do a get latest first, which in Git, is done doing a Pull.

And, when you do a Get Latest, you may get merge conflicts, and it is here the Git branches can help.

But first, let us see what we can do to get this to work nicely.

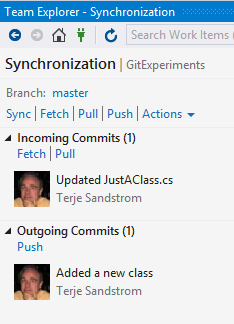

We can do a Pull immediately, and that may or may not trigger a merge. But we can also start with a Fetch. A Fetch is the first part of a Pull. From the Git Survival Guide you see that the Pull brings the commits from the remote all the way down to the workspace. A Fetch does the first part, it moves the commits from the remote in to the local repository, but does NOT move it into the workspace.

This is smart to do, since it makes it easier to see what these remote commits are, and if they possible could trigger some action on your side.

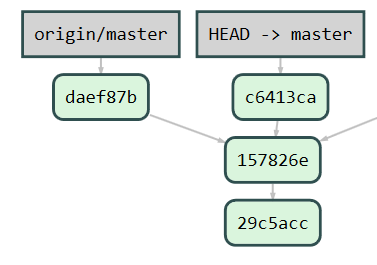

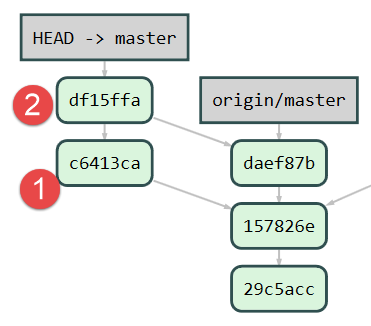

And we see that the commit from the remote updated an existing class, whereas we locally added a new class. This should not create any conflicts. But we do have a branching here that needs to come together:

And that must happen before we can push, so we have now no choice but to merge these two commits.

Merging in git is easy

Thankfully, Git merging is just as forgiving and easy as the branches, and we can merge any branches, we don’t even need to worry about how they are related. In this case we merge the two parts of the same branch, the local and the remote.

Normally we would do that using the Merge button in the Branches hub, but in this case we just trigger it by using the Pull button in the Synchronization hub. (We could have used the Merge here too, it is fully legal to merge a remote branch into a local, they both exist in our local repository).

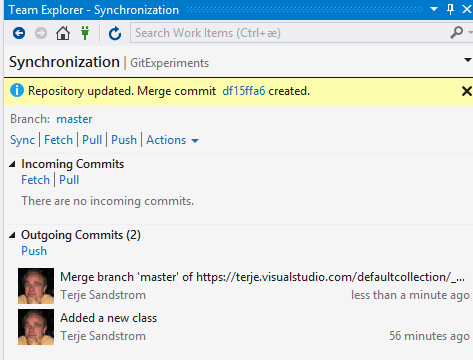

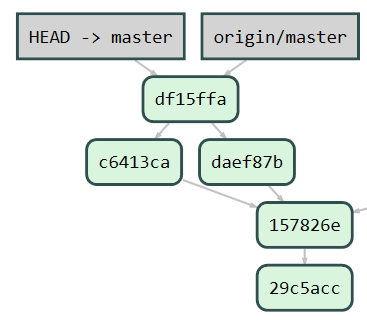

The merge worked with no conflicts, but we got another merge commit with the combined changes, and now we have two commits to push up.

The two commits marked 1) and 2) are the two we need to push up, if we do so, the remote master will be in sync with us. It is smart to do this as soon as possible, so that we don’t get more remote commits to merge in.

Note how the remote master branch pointer now have moved up along with the local master branch pointer. If you think “branches are pointers” it makes it easier to get a good grasp of this.

Small team working with local branches

Let us now assume that you didn’t really want to merge these changes in now, you wanted to 1) Just delay the merge, you didn’t feel ready 2) You wanted to share your code with another developer, but not the merged stuff 3) You wanted to just see if your changes still builds on the server build.

If you make it a habit of always working in a local branch, these things can be done, and also, it opens up more possibilities.

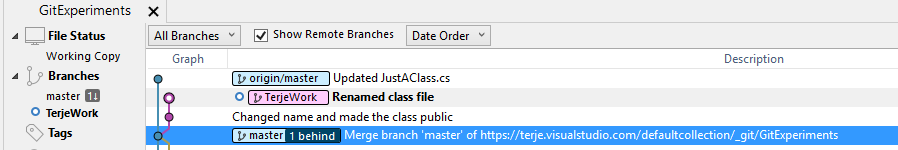

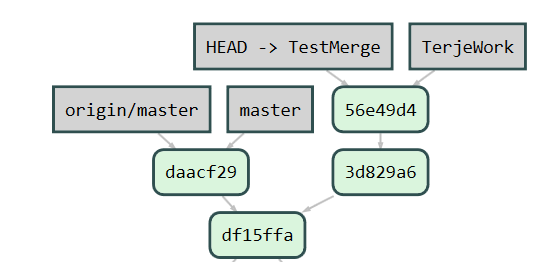

Now let us repeat using a new local branch, name it TerjeWork. Then we make a couple of commits in that branch. Now, we also have a commit added remotely to the master branch.

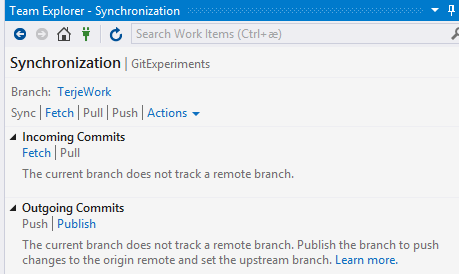

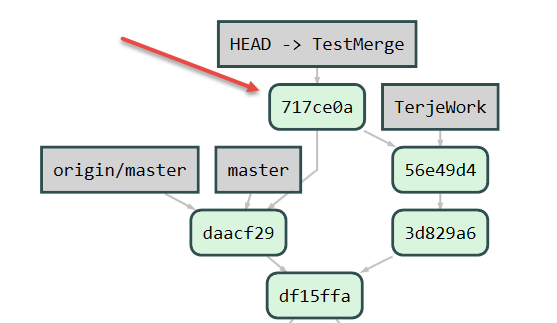

First, we don’t see ANY remote changes until we do a fetch. If we go to the Sync hub now, we will see that we have not published our branch, and if we do a fetch, nothing seems to be changed - in Visual Studio, but if we open up the same view in SourceTree, we will see the following

The fetch DID load down all the changes to our local repository, but Visual Studio only showed us only what was happening with respect to our local branch.

We can now switch over to the master branch and have a look at the changes there, and then determine if we WANT to merge or not.

We can also choose to publish the branch for one of the reasons above.

And, we can even merge the changes FROM master into our local work branch!

Let us assume that we are really uncertain how that merge will work. We don’t want to spoil our own work, and we don’t want to get into a corner with the master branch.

Using a local integration branch

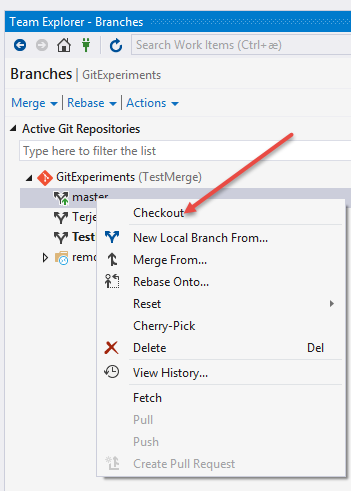

First we start with pulling the remote changes into local master, we don’t really need to do that, we could merge directly too, but it feels more controlled. To do this, switch over to the master branch You switch over by using the Checkout command:

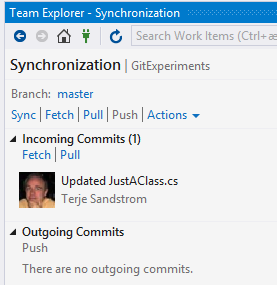

In the Sync hub you now see the incoming remote commit, and you choose Pull

Then switch back to the TerjeWork branch.

And then we create a new local branch from our TerjeWork branch, we call it TestTheMerge - we know it is only temporary, and the name doesn’t matter.

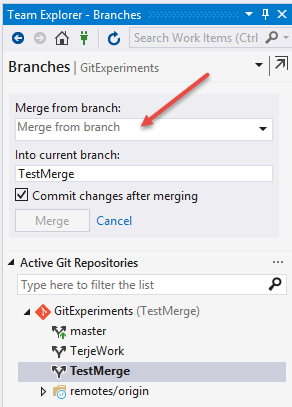

Now, on the Branches hub, select the Merge

And in the dropbox appearing, you choose the Master branch, and then press Merge

| Before Merge | After Merge |

|---|---|

|

|

You now have a branch and a commit which you can use to test the merge. If it works, you can then choose whether to merge it to your local working branch, or merge it back to master. If you merge it back to master, you can then merge master back to TerjeWork again, and then continue working.

Also note that you can choose to do nothing, after having looked at the master changes, and just continue working in your own branch. That is a very normal situation.

Some branching practices

Naming of branches

You can name a branch anything, and in Git that is rather normal. Due to the low cost of branching and merging, there is little consequence in making a new branch.

But there are some conventions for naming that could be wise to look into. We will look into these later, but names like GitFlow and GitHub Flow can be mentioned.

Grouping of branches

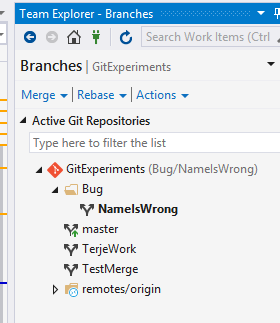

When talking about naming of branches, there is one trick that can be useful. A branch can be named with a backslash, and that causes the git UIs to treat what is in front of the backslash as a group or folder, and what is after the backslash as the branch name proper. The truth, mind you, is that the branch name is really the whole thing.

Assume we want to handle our bugs in a particular way, we want to keep an easy track of them, so we keep them in the same “group”, called Bug. When we then get a bug, we create a branch for the fix named like “Bug\NameIsWrong”. (We could even add the Workitem number here, alone or as part of the name of the branch, if that makes sense to us)

Let us create this branch and see how it looks:

Pretty nice ! And this also works in SourceTree

Deletion of branches

If you delete a branch in TFS, the code is gone too (not really all true, because it can be undeleted, if you didn’t purge it). In Git you always just delete the pointer. It is a common practice in git to delete branches.

Publishing branches

There is NO reason not to publish a branch in git. It does no harm, it doesn’t create or cause anything that can harm your project. In TFS VC the thinking is that branches are costly, and many TFS VC people hang onto that belief. Local branches is slowly accepted, but remote branches are still viewed as dangerous. Again, they are not.

Don’t publish ALL your branches

Even if there are no reason not to publish a branch, there is a good reason why you should keep local branches local. A published branch is available for everyone, and can’t always be changed afterwards (if you pushed your commits). A local branch can always be changed afterwards in different ways, it is called “rewriting history”, and it opens up some nice opportunities. More later on that too.